Dick Koontz easily rattles off the names of the exotic woods he’s used throughout the years to handcraft nearly every stick of furniture in his home.

“That’s my masterpiece,” Koontz said, pointing to a finely detailed grandfather clock occupying a place of honor in his living room. “That’s tiger maple; it’s called that because of the stripes.”

Indeed, the 7-foot clock is a beautiful piece, a crowning achievement for a self-taught furniture maker who’s been honing his craft for nearly 70 years.

Nearly every corner in every room of the two-story home he shares with Lu, his wife of 64 years, is adorned by his work.

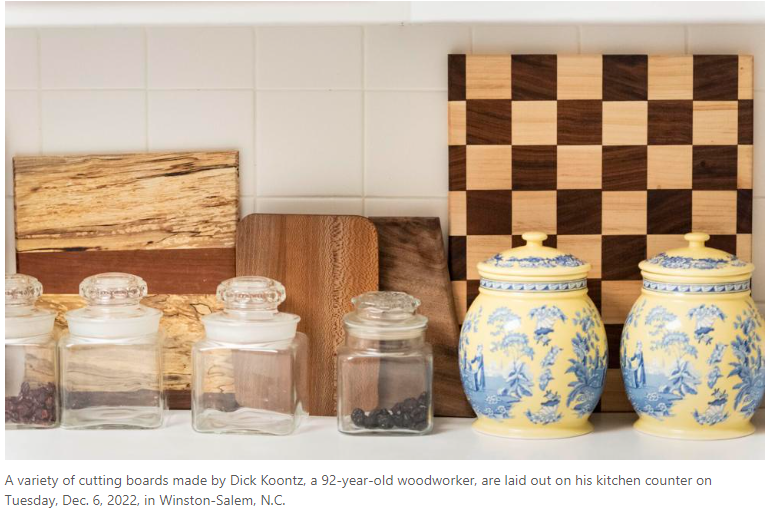

Some of his pieces — cutting boards and end tables, say — were easier to build than others. The high-boy dressers, a four poster bed and a slant-front desk with hidden drawers required more of his time and patience. Koontz, a modest 92-year-old who easily could have amassed a small fortune if he’d opted to sell his work, has a story about each piece.

But he didn’t spend a lifetime making fine furniture to pad his bank account.

Rather, his work — the tables, rocking horses, dressers, desks — even the ornate coffins tucked away in a corner of his basement — came about because he enjoys doing things for other people.

A patient soul

Koontz fell into furniture making in a rather straightforward way.

After doing his part with a hitch in the U.S. Navy during the Korean War, he enrolled at N.C. State with an eye toward teaching agriculture in high schools. He landed his first job in the late ‘50s in Stanley County and set to work.

“It was a little bit of everything from crops to mechanics,” he said.

And part of the curriculum included woodworking. He couldn’t very well teach woodworking if he didn’t know how to use a variety of saws and sanders.

It helped, too, that Koontz had the interest, natural aptitude and a love of learning that has spanned his lifetime.

He could figure out a lot of what he was doing by eyeballing and copying other designs; a voluminous collection of books and magazines provided a rich trove of ready reference materials.

If he couldn’t figure out, say, a particular technique for making claw feet or curving a desk drawer, he’d look it up and work on it until he mastered it.

Which, during a walking tour of his home in which he showed his work, begged the question: Have you always been a patient man or did woodworking teach you patience?

Before he could even get the answer out of his mouth — “I’ve always been a patient man” — Lu laughed out loud. “Oh, sure!” she said. A life partner always knows the truth.

The key to making good quality furniture, according to Koontz, is the material.

“If you’ve got pretty wood it makes pretty furniture,” he said. “Ugly wood makes ugly furniture.”

Of course — and Koontz wouldn’t say this himself — the best, most attractive wood in the world is just a pile of lumber without the eye and the skill of a craftsman who cares about his work.

Koontz has had wood shipped from all over the country over the years. The striped maple came from Oregon.

But he has been just as likely to cut local maples and make the boards himself. And he’s been caught more than once eyeballing neighbors’ yard waste.

Making furniture runs in the family. Koontz was happy to share the backstory about a dresser in his front hallway.

He didn’t make that one. He and Lu bought it in Koontz’ native Davidson County years ago, and when they got it home, they noticed a signature on the back.

William A. Heitman. May 3, 1863.

“My great-grandfather,” Koontz said. “He bought and moved a whole church to his farm to use as his workshop.”

Lu, too, knows the stories behind each piece of furniture. And on the rare occasions when Koontz’ memory sputtered, she patiently helped with the answer.

“Big leaf curly maple,” she offered when Koontz was looking for the name of a particular wood.

A life partner, after so many years, can sometimes help finish another’s thoughts.

Worthy backstory

Unhurried, a luxury of a man content in retirement, Koontz moved from room to room on his nickel tour, happy to share details.

That nick in a cabinet door? It came from a .22 bullet that was fired into a walnut tree before it was milled, giving the board — and the cabinet — some character.

A sleek wooden rocking chair on his screened in porch? He attended a workshop given by renowned furniture designer Sam Maloof and made an exact replica of one of his pieces. “The real thing, if you could find one, would cost you $100,000,” Koontz said.

Oh, and the cutting boards. Lu’s kitchen is lined with them, and Koontz has a storage cabinet filled with others downstairs. Each one is unique.

The quality of his work, the time he’s put in, the financial investment in quality tools and his exquisite eye for detail, as mentioned earlier, could have made a fine side hustle for an educator.

But Koontz would never hear of it. He made a lot of furniture for his three adult sons and his grandchildren. Friends, too.

Asked what he enjoys most about his hobby, Koontz didn’t hesitate. It wasn’t satisfaction from creating something so beautiful with his own two hands or making something that nature provided into pieces that will last for centuries the same way his great-grandfather did.

“Giving it away,” he said. “I like seeing the look on people’s faces when I do.”

While standing before his collection of tools in a very orderly workshop, Koontz responded to a small joke about how he must be good at woodworking because he still has all 10 fingers with a story.

He pointed to a SawStop table saw, a computerized tool that shuts off automatically if something other than wood touches its blade.

Several years ago, he had a dream, a nightmare really, that he’d cut himself badly. He shook it off and continued making things.

About a year ago, he found out the hard way that the saw works as advertised when his finger caught the blade and the saw shut down barely breaking his skin. “It paid for itself that day,” he said.

At the end of his tour, Koontz addressed the handcrafted caskets. They seemed an odd thing to make — until the backstory came tumbling out.

He’d made one, sized for a child, for someone he knew in California who feared they would have to bury a toddler.

When it turned out not to be needed — thank God — Koontz decided to give it to someone who might be under financial strain. One less thing for a distraught parent with enough heartache.

After several calls, Koontz learned of a local family who had lost a toddler in an accident.

A year later, once the family’s grief had lessened some, a handwritten thank you arrived in the mail. “I just can’t imagine … so horrible,” said Koontz, choking up and unable to finish his thought.

Having mastered the technique and with a supply of similar boards, he made two more coffins, his and hers, for he and Lu.

“Those things are expensive,” he explained, his wry sense of humor re-emerging. “Nobody’s getting out of this alive.”

The last stop on the tour took him to a quickly dwindling stack of boards near his workshop.

“When those are gone, I’m done,” he said. “I’ll get rid of all my tools then, too. Nothing lasts forever.”

Fwd: Dick Koontz Article

Inbox

| Jeff Warren | Dec 27, 2022, 7:44 PM (5 days ago) |   | |

to me, Meagan, Jason, Abbie, Michelle |

This is my cousin that made the cutting boards. I called him tonight and he told me about being interviewed by the paper. Read and watch the videos. I think you will enjoy this.

Dick is uncle Hoyle and Aunt Edrie’s son. Aunt Edrie was mama’s oldest sister. When Dick was born mama become an aunt when she was four years old.

Jeff Warren

(803) 413-0202 (Cell)

Begin forwarded message:

From: Doris Warren <Doris@warrenforensics.com>

Date: December 27, 2022 at 7:38:56 PM EST

To: Jeff Warren <Jeff@warrenforensics.com>

Subject:Dick Koontz Article

A master craftsman’s greatest joy is making others smile

https://journalnow.com/news/local/a-master-craftsmans-greatest-joy-is-making-others-smile/article_03cf7d48-77ba-11ed-8ff1-3b746888d8df.html

Doris Warren

Sent from my iPhone