Heralded as the next step in food production, this practice is gaining ground in the US. But are they really a greener alternative to traditional farming?by Victoria Namkung in San Francisco with photographs by Jim McAuley

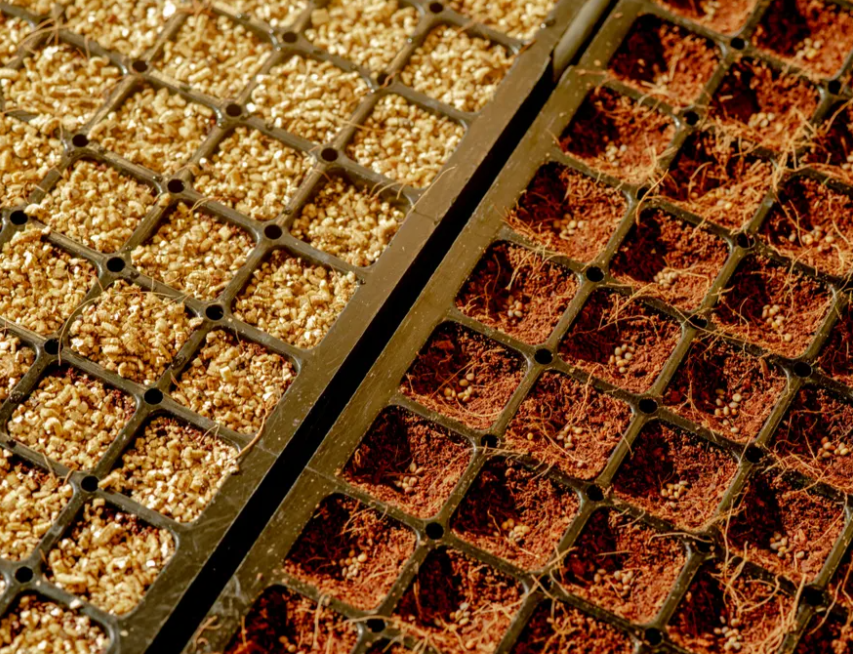

At a hyper-controlled indoor farm in industrial South San Francisco, four robots named John, Paul, George and Ringo carefully transfer seedlings from barcoded trays into 15-plus foot towers that are then hung vertically inside a 4,800 sq ft grow room.

Inside the hygienic space, which is operated by the indoor farming company Plenty, there’s no soil, sunlight or tractors, but rows of hanging crops illuminated by colorful LED lights and carefully monitored by cameras, sensors and artificial intelligence. Once a tower is ready to be harvested, a balletic automated process reminiscent of a dry cleaner’s conveyor belt begins.

A robot named Garfunkel (a nearby counterpart is called Simon) gently grabs and turns the tower on its side before setting it down to be trimmed by a machine. Workers in navy branded jumpsuits inspect the greens for any defects, but there are almost none. Then the pesticide-free product is packaged and put on a truck to be delivered to a local market where the customer becomes the first person to touch it.

Welcome to the world of indoor vertical farming, which, depending on who you ask, will revolutionize the future of agriculture in a warming world, or is a problematic climate solution due to its high energy costs.

“We’re moving into an age where climate change is changing what we grow and how we grow it,” said Nate Storey, Plenty’s co-founder and chief science officer. “Ultimately, I think we’re future-proofing agriculture for our species.”

With the world’s population expected to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050, most of whom will be living in cities, experts say it will require a 70% increase from current levels of global food production. But with agricultural land in short supply thanks to climate crisis and urbanization, it’s clear today’s food systems are not ready.

It’s estimated there are more than 2,000 vertical farms in the US growing produce such as lettuce, herbs and berries. Market leaders such as Plenty, Bowery, Kalera and AeroFarms – which can operate 365 days a year regardless of weather conditions – and sprawling greenhouses from companies like AppHarvest and Gotham Greens, see themselves as part of the solution. And investors clearly agree.

Indoor farming raised over $1bn in 2021, exceeding the combined funding generated in 2018 and 2019, and the industry is expected to grow to $9.7bn worldwide by 2026.

Earlier this year, Walmart announced an investment in Plenty as part of its $400m Series E funding round. The retail giant will source leafy greens for all of its California stores from Plenty’s new 95,000 sq ft flagship farm in Compton, California, which will open early next year.

Plenty will also be growing Driscoll’s strawberries indoors at their Laramie, Wyoming, research and development farm as part of a new agreement.

But critics say the massive energy costs needed to run vertical farms and greenhouses make the practice far less eco-friendly than their branding suggests and question how they can truly feed a world that relies on calories from grains such as soy, corn and wheat.

Ultimately, I think we’re future-proofing agriculture for our species

Nate Storey

Designed to produce yields hundreds of times larger than traditional outdoor farming, vertical farms occupy spaces such as buildings or shipping containers while using 70 to 95% less water since they can recapture and recycle water rather than waste it due to poor irrigation or evaporation. Products are fully traceable from seed to shelf, stay fresher longer and there’s little risk of bacteria like E coli, which led to large recalls of romaine lettuce in 2019 and 2020, since there’s no contamination from runoff water, infected animal feces or having to travel long distances in trucks and cargo planes.

Large-scale vertical farms are typically built near cities where greens can be bred for flavor rather than storage. With futuristic farming there’s no need for lettuce to sit inside a truck for days losing its quality and nutritional value.

California’s ongoing drought, the demand for locally grown food and the recent failures of the supply chain during the pandemic has made the practice, which is already popular in parts of Asia, Europe and the Middle East, especially attractive.

“What’s clear to me is that we’re living in an increasingly unreliable and uncertain world,” said Irving Fain, CEO and founder of Manhattan-based Bowery Farming. “We need to find certainty and reliability – and we need to act now.”

Bowery’s smart farms in the north-east collect billions of real-time data points via sensors and cameras that feed into machine-learning algorithms to provide their produce to more than 1,100 grocery stores, including Whole Foods, Albertsons, Safeway and Amazon.

In the process of trying to find solutions to vulnerabilities in the food system, entrepreneurs like Fain say they’re gathering the kind of knowledge about plant growth and agronomy that would take a traditional farmer outdoors hundreds of years to accumulate.

“We’re reimagining farming and reinventing the fresh food supply chain and rebuilding one that’s a lot simpler, safer, has much more surety of supply and ultimately it’s much more sustainable as well,” said Fain.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say the industry will replace, or even overtake, conventional agriculture.

Brandon Beh

But not everyone is as optimistic about indoor farming’s prospects.

Washington Post columnist and co-host of the Climavores podcast Tamar Haspel calls vertical farming “lettuce for rich people”. During a recent episode on vertical farms, Haspel and co-host Mike Grunwald highlighted the ways growing upwards indoors can bypass so many of the problems related to traditional farming, but say that the huge energy costs required to power vertical farms make them a “deal-breaker”.

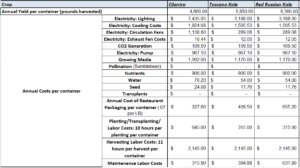

While Plenty, Bowery and other vertical farms don’t release data on how much energy they use, the 2021 Global CEA Census Report found that greenhouse growers used 15-20 times as much energy, on average, and vertical farms used a little over 100 times as much energy as outdoor lettuce growers in Arizona. The same report noted that smaller facilities had significantly higher energy use relative to larger counterparts.

Other experts aren’t so sure. Gail Taylor, the department chair of plant sciences at the University of California, Davis, said that while vertical farming is energy intensive in its current form, so is traditional outdoor farming.

“Sometimes we forget all the consequential effects like how many times you drive a tractor over a field or how many trucks you use to bring lettuce from the west coast to the east coast and fly food all around the world,” Taylor said.

Agriculture is already responsible for about 30% of total global emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and other planet-warming gasses. Researchers say cutting emissions from food is crucial in the fight to slow climate crisis.

Greenhouses have helped turn the Netherlands into the world’s second-largest agricultural exporter by value, sending over $10bn in tomatoes, cucumbers and bell peppers to neighboring countries such as Germany, Belgium and France in 2020.

But some Dutch greenhouses recently had to go dark or scale back production due to soaring power prices. About 8.2% of the country’s overall consumption of fuel is attributed to the glass structures, which require heating and artificial light to supplement sunlight.

While growing in controlled environments has been around since the 1970s, what made indoor vertical farming a reality in recent years was the significant drop in price of LED lights, which plummeted as much as 94% between 2008 and 2015.

The industry is counting on the grid continuing to get greener, which would drive power pricing down. “New energy sources will come online,” said Storey, of Plenty. “We’re going to see a massive and rapid evolution in the space that I think is going to shock people.”

Farms like Plenty and Bowery are already powered entirely by renewables, but Kale Harbick, a research agricultural engineer at the USDA who works on the optimization of controlled-environment agriculture, said it was important to understand the scale of the problem.

There are certainly benefits for renewables, but I wouldn’t call them a silver bullet

Kale Harbick

He said if you put a vertical farm in a skyscraper like the World Trade Center to grow lettuce and wanted to power it with renewable energy like solar, you would have to bulldoze the rest of the island of Manhattan to make room for panels to generate enough power just for the lights of that building.

“There are certainly benefits for renewables, but I wouldn’t call them a silver bullet,” he said.

Industry watchers say indoor farms have made big strides in recent years, and that it’s important to remember that we’re only at the start of the vertical farming journey.

“I believe that over the next 10 years, we will see the industry expand as vertical farms adopt more sustainable business models and the costs of vertical farming decrease,” said technology analyst Brandon Beh, co-author of a recent report by the technology company IDTechEx on vertical farming.

“Vertical farms do address a key consumer demand for fresh, organic produce,” Beh said. “However, I wouldn’t go so far as to say the industry will replace, or even overtake, conventional agriculture.”

While some ag-tech entrepreneurs believe they can grow almost anything indoors, others admit it’s not feasible to produce grain crops such as wheat or corn due to basic economics.

“Field crops are always going to be the best way to do calorie grains,” Harbick said.

Researchers are redesigning plants to grow in these new systems, so stone fruits, mushrooms, eggplants, peppers and cacao plants may be growing indoors in the near future.

About one-third of tomatoes are currently grown in greenhouses, but Harbick doesn’t see them being the right fit for vertical farms since they require 60% more electricity to grow than lettuce.

He said a diverse food supply system where some foods are grown in the field, some in greenhouses and some in vertical farms would be more resilient and robust.

Taylor said people need to start reimagining indoor farms as part of the circular economy, noting that other forms of renewable energy, like anaerobic digestion – a process through which bacteria break down organic matter like food waste – can be used to help power indoor farms.

Another solution would be to build vertical farms and greenhouses near decarbonizing industrial hubs that are trying to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, so farms could capture their heat and carbon dioxide to save electricity costs.

And while some farmers and scientists are critical about the influx of capital into the vertical and greenhouse farming space, saying indoor-grown food isn’t necessarily better for people or the environment, Taylor said it doesn’t need to be an either/or proposition.

“[Indoor farms] are never going to replace outdoor agriculture,” she said, “they’re only going to enhance it and make food supply systems better for the world.”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/aug/17/indoor-vertical-farms-agriculture